Ashdown Park Hotel, Gorey, Co. Wexford.

Jim O’Callaghan TD

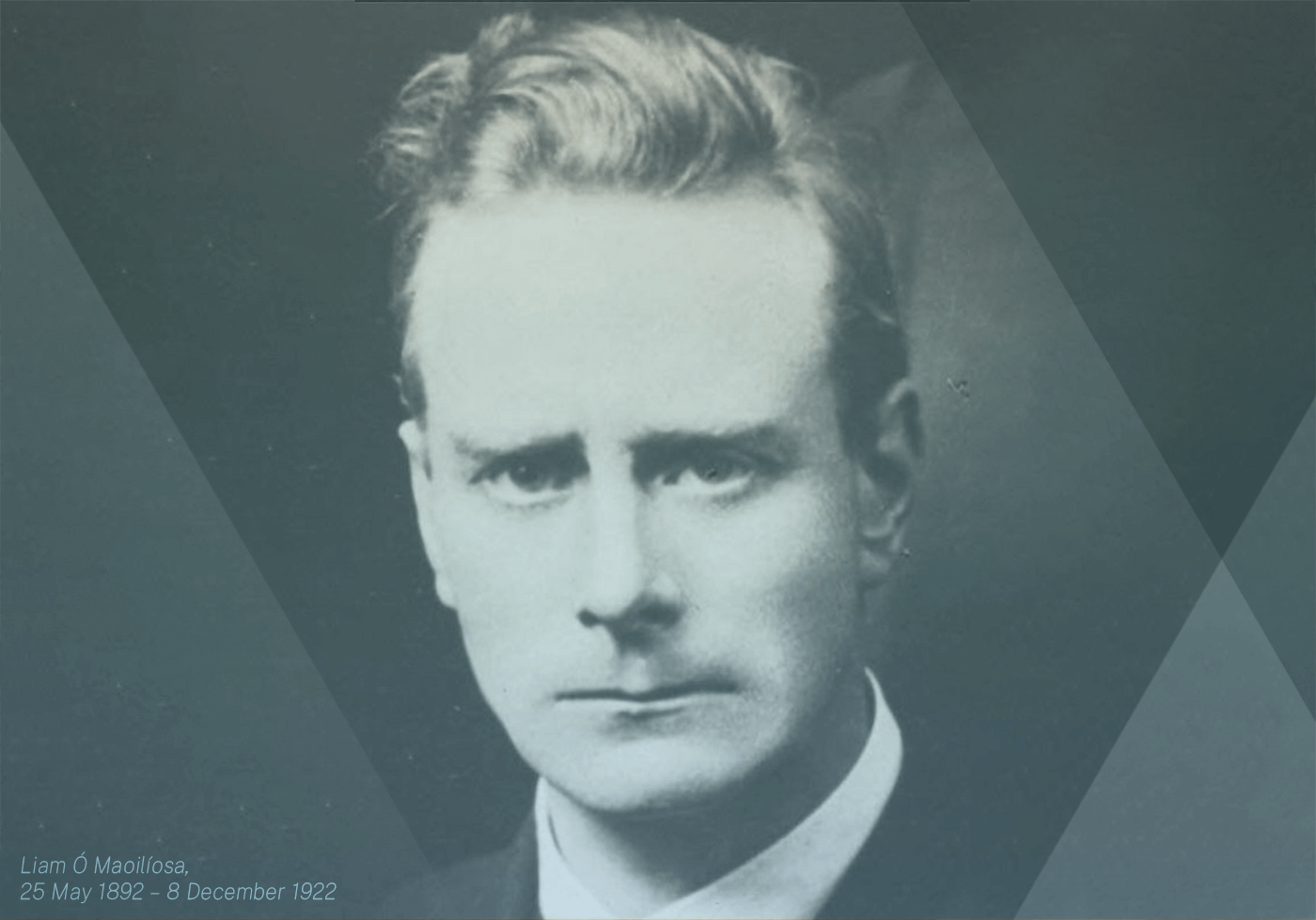

The Execution of Liam Mellows

I want to thank the Liam Mellows Commemoration Committee for the great honour of inviting me to address the official commemoration marking the centenary of his death.

At the time of his execution on 8 December 1922, Liam Mellows had been a prisoner in Mountjoy Prison for five months, having been arrested and imprisoned as one of the leaders of the anti-treaty IRA Garrison in the Four Courts.

He was executed by firing squad alongside Rory O’Connor, Joseph McKelvey and Dick Barrett.

Their executions by the Free State Government were in reprisal for the killing of Seán Hales TD by the IRA on 7 December 1922. Even though none of them could have had any involvement in Hales’ killing, the four were selected as representatives of each of Ireland’s provinces, with Mellows’ election for Galway in the 1921 general election qualifying him to fill that fatal role on behalf of Connacht.

Present at the execution was Canon John Pigott, one of the first army chaplains in the Free State Army, who subsequently recalled:

“In a few minutes we were all in the prison yard and the four, all brave and calm, were lined up before the firing squad. I gave a last absolution and as I was having a final word with Rory and Liam, I saw Liam shuffle the gravel from under his feet so that he could stand up more firmly. I moved a few yards to the right and as I did so I heard Liam Mellows say his last words: ‘Slán Libh Lads’ – his farewell to the firing party. In another instant the sign was given; the volley rang out; the men fell, and Canon McMahon and I anointed them where they lay on the ground.”

Notwithstanding the killing of Seán Hales on the previous day, the execution of Mellows and his colleagues received widespread condemnation. Later on the day of the executions the leader of the Labour Party, Thomas Johnson TD, questioned in Dáil Éireann whether any member of the Free State Government had any regard for the honour of Ireland or the good name of the state, and stated that he could not imagine that anyone could defend the action, save on grounds of vengeance:

“You were charged with the care of those men; that was your duty as guardians of the law. You could have charged them with an offence. You held them as a defence, and your duty was to care for them. You thought it well not to try them, and not to bring them to the Courts, and then, because a man is assassinated who is held in honour, the government of this country announces apparently with pride that they have taken out four men, who were in their charge as prisoners, and as a reprisal for that assassination murdered them. These men, unless with the connivance of the government, could not have been engaged in any conspiracy when they have been in your charge for five months….There is no pretence of legality; there is not even the trial guaranteed under the rules authorised. The offence these men committed was an offence committed before July. So far as we know there has been no trial, and these men were executed as a reprisal.”

The executions not only raised serious questions about the legality of the actions of the Free State Government but also its competence. Cathal O’Shannon, TD for Louth and Meath, challenged the Free State Government’s competence by stating:

“I say that you are not able to carry on the government of this country. You would not be forced to the necessity, as you call it, of murdering the four men in Mountjoy this morning if you were competent. You would not. Instead of being able to follow up the assassins of Seán Hales and capture and try, and execute them for murder, you would not be forced, if you were competent, to go into Mountjoy and take four prisoners you had in your hands for four or five months.”

During his contribution O’Shannon specifically referred to Mellows and asked whether any government TD was aware of the impact he had in Ireland during the previous decade:

“Do you know that there is not a little nipper in the Fianna since 1912 right down to today, from the age of 8 years to 18 or 20 years, who will grow up within the next three years with nothing in his heart but revenge for the death of Liam Mellows?”

Responding on behalf of the Free State Government, Richard Mulcahy TD, Minister for Defence, said:

“The action that was taken this morning was taken as a deterrent action, taken to secure that this country shall not be destroyed and thrown into chaos by the toleration of any group of men acting together for the destruction, one by one, or in groups, of those single representative people that are the keystone of our government and of our society here.”

Kevin O’Higgins TD, Minister for Home Affairs and Vice President of the Government, justified the executions by claiming that there were no real rules of war and that the safety and preservation of the people was the highest law.

Nonetheless, the illegality of the executions was recognised in the official report from the Free State Government which stated that the four had been executed:

“as a reprisal for the assassination of Brig Hales TD, as a solemn warning for those associated with them who are engaged in the conspiracy of assassination against the representatives of the Irish people.”

Opponents of the Treaty and members of the anti-treaty IRA viewed the executions as nothing less than murder, a view widely shared by international media. For instance, the New York Nation of 20 December 1922 described them as “murder foul and despicable and nothing else”.

Even that renowned propagandist for the Free State Government, P.S. O’Hegarty, accepted that “these reprisal executions were illegal.”

Was Liam Mellows a Revolutionary Socialist?

Unfortunately, the memory and contribution of Liam Mellows in Irish politics have been dominated by the impact his unlawful execution had on Irish politics during and in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Nonetheless, the outrage caused by his execution should not overshadow the political contribution and significance of his life.

As is apparent from the selected writings of Liam Mellows that have been excellently compiled by Conor McNamara in his Liam Mellows, Solider of the Irish Republic, published in 2019, Mellows played a significant role in the struggle for Irish independence and left behind a small but important body of writing that provides us with an insight into one of the most interesting, yet marginal, figures from the revolutionary era.

This address seeks to examine Liam Mellows’ contribution as a prominent and consistent opponent of imperialism, and how his anti-imperialist views were part of an international campaign that correctly and presciently viewed imperialism as the real obstacle to the self-determination of people subjected to colonial rule.

This is the contribution of which Liam Mellows and those who shared his political ideology can be proud, particularly as the negative legacy of empire has become increasingly more apparent in recent times.

The 1916 Rising and the War of Independence constituted a revolution against British rule in Ireland. Although socialists were involved, it was not a socialist revolution. As a country that had not developed an industrial base, it is unsurprising that a conflict between labour and capital was not at the forefront of the minds of those who espoused Irish independence.

Nonetheless, there were many, particularly James Connolly and subsequently Peadar O’Donnell and Ernie O’Malley, who viewed the Irish revolutionary struggle in predominantly class terms. Liam Mellows has frequently been viewed as a revolutionary socialist and, consequently, has also occupied a revered place for many on the Republican left. In part, this is due to the hagiography on Mellows written by the socialist republican C.Desmond Greaves.

However, it is questionable whether Mellows was, in fact, the revolutionary socialist that some have sought to portray. More probably, he was a radical anti-imperialist who viewed republicanism as the most appropriate method of destroying the imperialism he detested and that had created so much of the inequality and suppression of national identity that he witnessed.

It was only in the last five months of his life whilst a prisoner in Mountjoy Prison that Mellows produced writings that have been interpreted as being the writings of a revolutionary socialist.

The most compelling evidence of Mellows socialist leanings is provided in the article he wrote for the Workers Republic, the newspaper of the Communist Party of Ireland, on 22 July 1922. This article is a scathing attack on the Labour Party, motivated in part by the fact that anti-treaty Republicans believed that Labour’s failure to support their campaign was a betrayal of working people.

His condemnation of the Labour Party for purporting to seek a Workers’ Republic whilst accepting the terms of the Treaty can, no doubt, be read as suggesting that the pursuit of a Workers’ Republic was Mellows’ objective. In criticising the Labour Party, he stated:

“The Irish Labour Party talked glibly of a Workers’ Republic. It still pretends to have as its objective the establishment of such a State. Veiled threats of a big stick it intends to wield some day are thrown out for the credulous. Professing to be against militarism, its leaders try to delude the movement into believing that at some future date they will head a revolution.

Labour played a tremendous part in the establishment and maintenance of the Republic. Its leaders had it in their power to fashion that Republic as they wished – to make it a Workers’ and Peasants’ Republic. By their acceptance of the Treaty and all that it connotes – recognition of the British monarchy, British Privy Council and British Imperialism; Partition of the country and subservience to British capitalism – they have betrayed not alone the Irish Republic but the Labour Movement in Ireland and the cause of the workers and peasants throughout the world.”

It is probably more accurate, however, to suggest that Mellows’ real motivation in writing this article was his abhorrence of British imperialism rather than his devotion to a Workers’ Republic and his disbelief that those seeking the establishment of a Workers’ Republic would align themselves with a treaty arrangement that continued to support and endorse the constituent parts of British imperialism in Ireland. He viewed the Free State created by the Treaty as such a part:

“It is a fallacy to believe that a Republic of any kind can be won through the shackled Free State. You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. The Free State is British created, British controlled and served British Imperialist

interests. It is the buffer erected between British Capitalism and the Irish Republic. A Workers’ Republic can be erected only on its ruins. The existing Irish Republic can be made the Workers’ and Peasants’ Republic if the Labour movement is true to the ideals of James Connolly and true to itself.”

The high point of Mellows as revolutionary socialist is his article’s assessment of the significance of the Irish Republic:

“The Irish Republic represents independence and the struggle has a threefold significance. It is political, it is intellectual, it is economic. It is political in the sense that it means complete separation from England and the British Empire. It is intellectual in as much as it represents the cultural expression of the Gaelic mind and Gaelic civilisation and the removal of the impress of English speech and English thought upon the Irish character. It is economic because the wresting of Ireland from the grip of English Capitalism can leave no thinking Irishman with the desire to build up and perpetuate in this country an economic system that had its roots in foreign domination….The Irish Republic stands therefore for the ownership of Ireland by the people of Ireland. It means that the means and processes of production must not be used for the profit or aggrandisement of any group or class. Ireland has not yet become industrialised. It never will if, in rejecting and casting off British Imperialism (and its off-spring the Free State and Northern Parliament) the Irish Workers insist that a native imperialism does not replace it. If the Irish people do not control Irish industries, transport, money and the soil of the country, then foreign or domestic capitalists will.”

These writings fit fairly comfortably within a socialist perspective of the Irish revolutionary period and Mellows may have had a late conversion to the socialist cause as a result of his five-month imprisonment in Mountjoy.

What is more likely is that this article illustrates that his longstanding and consistent anti-imperialism was outraged by what he viewed as a Labour Party that was prepared to sustain and support a Free State that he viewed as a creation of British imperialism.

Probably a more accurate assessment of Mellows’ politics is not that he was a revolutionary socialist but that he was primarily an anti-imperialist who was committed to tearing down the imperialist structures that dominated life in Ireland and Europe at that time.

Support for this analysis comes from Mellows himself who was aware that his article in the Workers Republic was being presented as support for a socialist uprising.

In a letter to Seán Etchingham he rejected as silly the suggestion that what he described as these “hastily written outline of ideas” could be branded as “communistic.”

The International Anti-Imperialism of Liam Mellows

The consistent and dominant political ideology that is apparent from the writings and speeches of Liam Mellows is anti-imperialism. Although his politics were formed by the actions of the British Empire in Ireland, his detestation of imperialism went beyond that of its involvement in Ireland. At a meeting in New York’s Central Opera House in November 1918 Mellows told the large crowd:

“The Romanovs are gone, the Habsburgs are gone, the House of Hohenzollern is gone and then it is said that there is peace because the power of the German Empire is broken. But there can be no peace until another Royal House, the House of Hanover – pardon me, I mean Windsor – is gone and with it all the English Aristocrats – the Lansdownes, the Milners, the Balfours – and the power of another empire that rode roughshod over the peoples of the world, the British Empire,

is gone. When that occurs, the world will be liberated from the foulest tyranny that has ever cursed it, and from its ruins will arise a free Ireland, a free India, a free Egypt, a free Africa.”

Earlier on his American visit, he gave a speech at the Washburn Theatre, Chester, Pennsylvania on 23 April 1918 where again he sought to internationalise the Irish struggle:

“The Irish people stand for a cause that is as great as that of any race; a cause as great as that which Belgium stands for; a cause as great as the liberty of Serbia and Montenegro. They stand for a cause which has lived for longer than that of any of these other countries, because Belgium and Serbia have been persecuted for three years, and Ireland has suffered for 750 years.”

He then positioned Ireland as being integral to the imperial expansion of England. He suggested that Ireland became the jumping off place for the expansion of the British Empire and that the foundations of the British Empire were laid in British policy in Ireland:

“England has very good reasons for keeping Ireland down. The very future and safety of her Empire depends on her holding Ireland. If proof were needed, we have a very recent statement made by an organisation known as the British Navy League, composed of Officers of the British Navy. In a memorandum presented to the British Cabinet several months ago, they stated that the position of Ireland is vital to England, because Ireland contains 18 harbours, possession of which by England is necessary in order that England control the trade routes of the world. Further on, they state that Ireland is the Heligoland of the Atlantic. You will find therein the reason why England keeps Ireland down; Ireland being the Heligoland of the Atlantic is necessary for England’s own aggrandisement.”

Mellows’ subsequent opposition to the Treaty was consistent with his anti-imperialist views and was based on his assessment that the Treaty was a product of the British Empire which he viewed as representing “nothing but the concentrated tyranny of ages.” In his speech to Dáil Éireann on 4 January 1922 opposing the Treaty he framed his opposition within a condemnation of the British Empire:

“Under this Treaty the Irish people are going to be committed within the British Empire. We have always in this country protested against being included within the British Empire. Now we are told that we are going into it with our heads up. The British Empire stands to me in the same relationship as the Devil stands to religion. The British Empire represents to me nothing but the concentrated tyranny of ages….It means to me that terrible thing that has spread its tentacles all over the earth, that has crushed the lives out of people and exploited its own when it could not exploit anybody else. That British Empire is the thing that has crushed this country; yet we are told that we are going into it now with our heads up. We are going into the British Empire now to participate in the Empire’s shame even though we do not actually commit the act, to participate in the shame and the crucifixion of India and the degradation of Egypt. Is that what the Irish people fought for freedom for?”

Mellows was correct in his criticism and condemnation of imperialism in general and the British Empire in particular because of the oppression, discrimination and racism upon which they were built. In this regard, his political ideology aligns comfortably with more recent historical assessments of the tactics and devastating consequences of imperialism.

Those tactics used in the expansion of the British Empire both before and after the American War of Independence were similar to the tactics that were used consistently in Ireland. An integral part of maintaining imperial control was the use of violence against native populations. In the imperial mindset of Rudyard Kipling these were the “savage wars of peace”. As Caroline Elkins illustrates in her History of the British Empire Legacy of Violence, skin colour became the mark of difference between those in the Empire who were viewed as civilised and uncivilised. She notes, however, that in Ireland and indeed within the Afrikaner population of South Africa skin colour was not the marker of local populations differences. Instead, it was a constructed skin colour:

“In effect, Britain radicalised the Irish and Afrikaners, equating their cultures to those of brown and black subjects, sometimes using dehumanising language to describe their physical appearances and living conditions, and believing that just like the Xhosa of South Africa or the Chinese in Malaya, the Irish and Afrikaners were “backward” populations that needed to be civilised.”

Oppression and violence became a central part of the British Empire’s control of its colonies notwithstanding the fact that many of its imperial defenders viewed its mission in a positive light as being a civilising mission. Even if such a benign interpretation is in part accepted, it is hard to avoid the conclusion reached by Elkins when she writes:

“If Britain’s civilising mission was reformist in its claims, it was brutal nonetheless. Violence was not just the British Empire’s midwife, it was endemic to the structures and systems of British Rule. It was not just an occasional means to liberal imperialisms end; it was a means and an end for as long as the British Empire remained alive. Without it, Britain could not have maintained its sovereign claims to its colonies.”

In fairness, there was also awareness at the time of Ireland’s independence, including amongst historians, of the oppressive impact of imperialism. Dorothy Macardle concluded her major work The Irish Republic in 1937 by noting how political thought was then advancing in Britain:

“The exploitation of the weak by the strong has been named by its just name, aggression; the law of the jungle falls into disrepute; a generation of Englishmen with new ideals of State craft is taking the reins of power.”

This international view of imperialism that was at the forefront of Mellows’ political thinking was influenced, as can be seen in his writings and speeches, by global events, particularly those that occurred after the end of the First World War.

Consequently, Mellows and the Irish Independence struggle receive a more accurate and fairer appraisal when the events of one hundred years ago in Ireland are viewed in the context of those other significant global events.

The Irish independence struggle was not only impacted by global events but also influenced them.

This latter view was recognised by Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who noted that “if we lose Ireland we have lost the Empire.”

This international nature of the Irish Revolution has also more recently been recognised in The Irish Revolution A Global History where the editors in their introduction note:

“The Irish Revolution, then, was fundamentally a transnational event. Funds for the Republican movement poured in via the expanse of networks of diaspora nationalism; its leaders, in both their ideologies and their military tactics, were profoundly influenced by experiences abroad; and the violence that defined events in Ireland between 1916 and 1923 emerged against a backdrop of comparable revolutionary and anti-colonial movements elsewhere in Europe and around the world. Despite emerging in such a fundamentally international context, much of the foundation or historiography on the revolution engages only tangentially, or not at all, with its inherent transnationalism.”

Liam Mellows’ Legacy and Cultural Equality

To where then does the anti-imperialism of Liam Mellows from a century ago direct those who are, or view themselves as, his political successors? What can members of Fianna Fáil learn from the life of Liam Mellows one hundred years after his execution?

We will never know whether Mellows, like so many others who opposed the Treaty, would have continued to align himself with Éamon de Valera after he had left Sinn Féin and established Fianna Fáil in 1926. But we do know that Fianna Fáil was founded four years after Mellows’ death by people who shared his belief that imperialism had inflicted grave damage on the Irish people.

They believed that the Irish people should be entitled to determine their own governance and their own future free from external influence and the societal hierarchy imposed by imperialism. It was this anti-imperialism that was one of the defining characteristics of Fianna Fáil in its early years.

In trying to decipher Liam Mellows’ legacy it is useful to start by developing an accurate assessment of the international impact of imperialism and the damage it inflicted on many colonised countries.

This damage was recognised very recently by the President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, in his speech to the Houses of Parliament on 22 November 2022 where he noted that the relationship between Great Britain and South Africa was “a relationship that was founded in colonialism and conflict, dispossession and degradation”.

Today, the legacy of imperialism can be seen in many countries whose governance and welfare continue to be damaged by the consequences of imperialism. At the heart of imperialism was the promotion of a political agenda and form of governance that was founded on supremacy and inequality, particularly cultural inequality.

The impact and effect of this cultural inequality in Ireland is now subsiding because as a country it has successfully unburdened itself of most, although not all, of the damaging consequences imposed by imperialism, and has attempted to do so by promoting the principle of equality.

Equality has a specific legal meaning as is apparent from the status afforded to it in many fundamental legal documents.

The 14th amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted on 9 July 1868, contained an equal protection clause which required that no State shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The Weimar Constitution of 1919 set forth individual rights of Germans, one of which was equality before the law.

The Irish Free State Constitution contained no equality provision but Article 40.1 of de Valera’s Bunreacht na hÉireann provides that “All citizens shall, as human persons, be held equal before the law”. More recently, equality as a rule to prohibit discrimination was given further recognition in the European Convention of Human Rights that contains a direct prohibition of such discrimination and the EU Charter on Fundamental Rights that contains a Chapter on Equality.

Most of these measures have ensured that the implementation of equality by states is limited to ensuring that the operation of their laws do not discriminate.

Equality in politics is a more nebulous ideal with an elastic political meaning that focuses mainly on economic equality and/ or cultural equality.

Economic equality assesses the manner by which resources and capital are distributed in order to lessen or reduce differences in wealth. On the other hand, cultural equality seeks to ensure that cultural differences are respected in order to achieve equality.

Consequently, economic equality seeks to achieve convergence whilst cultural equality seeks to recognise and respect divergence. In effect, cultural equality presents the principle of equality in a way that acknowledges and celebrates differences.

The partition of Ireland in 1921 was an event that most certainly did not acknowledge and celebrate differences. Instead it undermined any notion of cultural equality by dividing people living on the island based on their religious and cultural differences.

It was a crude imperial measure but one that was not unique to Ireland. The partition of India was also imposed by a departing British government as a measure to resolve what it perceived would be internal nativist unrest. It resulted in widespread migration and sectarian violence.

Although today Pakistan and India are viewed as being necessarily separate, this should not prevent an accurate assessment of the reasons behind the use of partition. As Yasmin Khan noted in what was probably the finest work on the partition of India:

“The partition of 1947 is also a loud reminder, should we care to listen, of the dangers of colonial interventions and the profound difficulties that dog regime change. It stands testament to the follies of Empire, which ruptures community evolution, distorts historical trajectories and forces violent State formation from societies that would otherwise have taken different – and unknowable – paths. Partition is a lasting lesson of both the dangers of imperial hubris and the reactions of extreme nationalism.”

Partition in Ireland resulted in less chaos than India but it did result in migration and sectarian violence. It also ensured that Ireland did not take a different, and unknowable, path. However, the paths that were taken are known and can be assessed with the benefit of 100 years of knowledge.

Both paths encountered very rough terrain for the first 75 years but any objective assessment of the paths taken must conclude that the path of independence is now a more economically successful, politically stable and culturally diverse path.

Although the risks associated with independence were enormous, the changes that have occurred in global politics during the past century, where cultural equality has overwhelmed imperialism, have empowered and vindicated that path.

The unknowable path down which the island did not proceed 100 years ago may have included more migration and more sectarian violence.

Today, however, as a result of the diminution of extreme nationalism and extreme loyalism, the motivation and basis for such violence no longer exists amongst the vast majority of reasonable people resident on the island who now overwhelmingly support the principle of cultural equality.

The dangers and fears that prompted the partition of Ireland are no longer present, although the sectarianism that existed on the island a century ago has regrettably survived within Northern Ireland where the external influence of global politics has been slower to penetrate.

The effect of partition was that cultural inequality was imposed throughout the island because it was believed that an independent Ireland could not accommodate different cultures and religions. Instead, two jurisdictions were created where cultural equality was viewed as being unnecessary. Today, it is accepted that cultural respect and recognition is essential in order to achieve cultural equality.

This was recognised by the Canadian Supreme Court in Andrews v Law Society of British Colombia ISCR 143 where the Court said that “The accommodation of differences is the essence of true equality.” Or as Professor of Political Theory, Judith Squires, has written:

“Equality now appears to require a respect for difference rather than a search for similarities. It also tends to focus on the importance of equality between groups rather than between individuals, incorporating an analyses of the systems and structures that constitute and perpetuate the inequalities under consideration in the first place.”

In considering what role equality can play in assessing the continuation of partition, it should be acknowledged that it is extremely difficult to discuss this issue objectively without being influenced by the politics of its imposition.

Similarly, any debate about Irish reunification has, to date, been framed too much in the context of Ireland’s past. Since the negative consequences of our shared and difficult history with Britain are now subsiding and the politics of imperialism have been overtaken by the political imperative of cultural equality, it is now time for those who wish to see an end to partition to frame that issue in the context of the promotion of cultural equality on the island.

In doing so, the negative impact of partition as a colonial measure should neither be ignored nor airbrushed from history, but its relevance for the future should be acknowledged as being limited. Inevitably, there will be groups in Ireland who will continue to see partition through the past rather than the future but that should not dilute the fact that the only legitimate reason to end partition is in order to see an improvement in the lives of people on the island, not to address an historic grievance.

Promoting Equality through Reunification

Fianna Fáil wants to see a united Ireland. It is the party’s primary aim and objective . Members of Fianna Fáil should not be hesitant or diffident about expressing this political ambition and how they think it can best be achieved.

Frequently in politics the easier and less risky path for an established political party is to seek no change until change becomes inevitable.

That is not a path that Fianna Fáil can follow. As a party that has played a defining role in Ireland’s progress over the past 100 years, Fianna Fáil must be central to the debate about any constitutional change on the island. It is a difficult and complicated issue but because of the terms of the Good Friday Agreement it is an issue that will not fade from the political agenda. If Fianna Fáil fails to lead this debate, it will be dominated by other parties and political groupings whose respect for consent and commitment to cultural equality may not be as inclusive as Fianna Fáil’s.

In truth, Fianna Fáil has a responsibility to all groups on the island, many who would never vote for it, to lead this debate. It also has a duty to its members because a political party that does not campaign for change in order to achieve its objectives will be viewed as passive.

If Fianna Fáil is serious about seeking to achieve Irish reunification it needs to recognise that cultural equality will be an absolute necessity in order to alleviate concerns that many in Northern Ireland have about a unitary state. Cultural equality in this context will mean that the cultural and religious differences of people on the island will need to be identified as meriting special protection.

Although Ireland in 2022 is culturally, religiously and ethnically much more diverse than it was one hundred years ago, the main resistance to reunification still emanates from those who believe their cultural loyalty to Great Britain and its Monarch will not be protected in any new unitary state.

A clear commitment to protect and recognise such cultural differences will be necessary in order to illustrate the benefits that can arise through reunification and to provide comfort to those who have legitimate concerns about the influence any new unitary state may have on their cultural or religious identity.

The success of the Good Friday Agreement is that all elected political groups on the island now recognise that any constitutional change in Northern Ireland is a matter for the people of Northern Ireland. Fianna Fáil for many decades before the Agreement fully accepted this principle of consent. To date, there has been no majority within Northern Ireland for Irish reunification and this has been and must continue to be respected.

However, if that changes in the future, then a necessary corollary to the respect that peaceful nationalists have shown for Northern Ireland’s position within the United Kingdom is that unionism must respect the wish of the majority of people in Northern Ireland to become part of a united Ireland. It is not a political path down which Unionists wish to travel but in a world where democracy needs to be protected it would simply be perverse if such a mandate from the majority of people in Northern Ireland was not openly respected.

In seeking to persuade the people of Northern Ireland of the benefits of reunification, a guarantee of cultural equality for all groups on the island will ensure that the failure of both jurisdictions in the aftermath of partition to respect the rights of minorities will not be repeated.

Ireland and its revolutionary struggle was an inspiration to other colonised countries that sought and achieved their independence.

Few have progressed as strongly and successfully as Ireland. More importantly, few have changed as significantly and unpredictably as Ireland.

The imposition of partition a century ago was a response to the politics that then existed in Ireland and the world. But those politics are now gone. The fall of imperialism and the rise of equality, particularly cultural equality, are two of the most significant political changes of the past century.

Unfortunately, the violence inflicted in the past has cast a dark and influential shadow, but in recent years that darkness has lessened because of the success of politics. As we gather here to commemorate the violent death 100 years ago of Liam Mellows, we should also be positive in the knowledge that next April we will celebrate the Good Friday Agreement where it was agreed that political differences and challenges on this island cannot and will not be resolved through violence but only through respect, debate and democracy.

It would be an inspiration to many countries that are marred by sectarian violence and political division if the people of a post-colonial country, partitioned through colonial intervention, decided in their collective best interests to reverse that partition and unite again in order to promote and protect their diversity.

Should this be achieved, Ireland would certainly have completed a remarkable and unpredictable colonial journey that concluded with its people being in a stronger position because of their ability to respect diversity and protect cultural equality whilst recognising their overwhelming common interest and similarities.

That would be a unique international achievement.