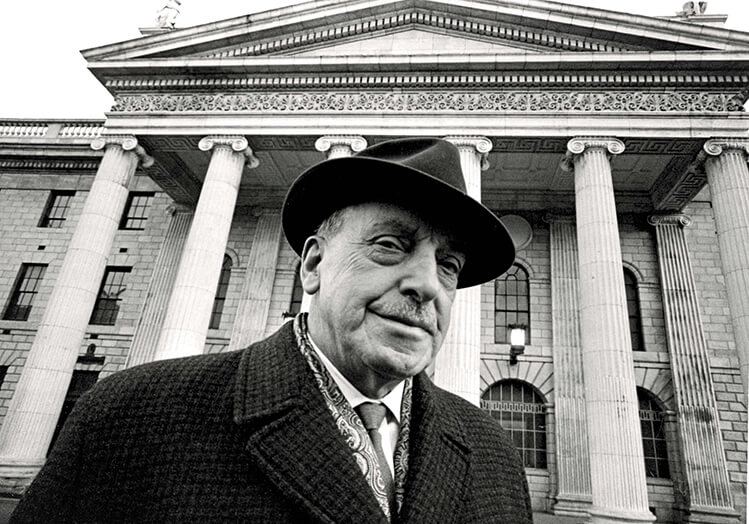

I want to thank the family of Seán Lemass for asking me to speak at this event. It is appropriate that the death of Seán Lemass, 50 years ago today, is marked and that his life is celebrated. For members of his family, today is a day to recall a loving grandfather and great-grandfather. For the wider public, today is a day to recall and acknowledge the political career and contribution of a man who had a transformative effect on Irish political and economic life. There were many phases in the public life of Seán Lemass – from the revolutionary era to his term as Taoiseach – but the phase of his life that was most impactful and influential from Ireland’s point of view was the 1950s and early 1960s. That was when decisions were made by Lemass which subsequently changed the direction of this country with long lasting beneficial effects.

The origins of the national transformation that he instigated can be traced back to the decade after the Second World War. That was an extremely difficult time for Ireland as is evidenced by the very limited achievements of the different governments during that period. As Minister for Supplies during the Second World War, Lemass saw the limitations that tariff barriers and protectionism had imposed on Ireland. Others opposed protectionism but it was his recognition of its limitations that ultimately lead to its collapse.

It seems inevitable to us in the twenty first century that Ireland in the second half of the twentieth century would transform itself from an agrarian based society and economy into a highly educated knowledge based society and economy. It must be emphasised, however, that there was nothing inevitable about that at the time. Ireland could have gone the same route as some of the post-soviet union republics and remained as a low production agrarian based society. That is what most would have predicted at the beginning of the 1950s.

Alternatively, Ireland could still have changed economic direction and yet seen its economy weaken in a similar way to how the economy of Northern Ireland has 2

regressed since partition. Had that happened we would find ourselves today, 100 years after partition, having a serious conversation as to whether our decision to leave the United Kingdom was the correct one. The success of Ireland as an independent country is, in part, evidenced by the fact that no serious commentator today, no matter what their political viewpoint, has contended that it was an economically damaging decision for Ireland to have established itself as an independent country. The policies of Seán Lemass in the 1950s and 1960s ensured that was not the case and that Ireland became a successful independent country.

It is important to recall that it was a widely held view in the 1950s that industrialisation and economic development were neither feasible nor appropriate for Ireland. For instance, in October 1955 the Irish Times published a very negative editorial about Lemass entitled “The Wrong Accent” in response to one of Lemass’ pro industrialisation speeches. The newspaper suggested that his proposals were an undesirable reversal of Fianna Fáil’s economic policy. It stated:

“Mr Seán Lemass will have to do better if he hopes to bring Fianna Fáil back to power on the strength of a programme. The programme that he detailed before the combined councils of the party organisation in Dublin last night is not only, in one respect anyhow, a reversal of traditional Fianna Fáil policy – which may or may not be a good thing – but seems to us to be based upon a fundamental error… What we do not like about his programme is that it sees the country’s future prosperity as dependent entirely on an increase in manufacturing industry. He says as much: “It is safe to assume that most, if not all, of the new jobs required to attain full employment must be found in non-agricultural occupations.“ Surely this approach is not merely wrong in fact but full of danger. The proper course is surely to work for the rehabilitation of agriculture and at least a doubling of its productivity, rather than to concentrate on manufacturing industries which have no root in our own resources. Has Mr Lemass – and has his party, if he speaks for it – abandoned all hope of a unified Ireland, which might find itself disastrously overstocked with manufacturing industry?”

Notwithstanding the widespread opposition to changing economic course, Lemass persisted and, along with TK Whitaker, recognised that Ireland’s economic direction needed to change. It was fortunate for Ireland that Lemass’ election as Taoiseach in June 1959 occurred a number of months after the publication of the “First Programme for Economic Expansion” in November 1958.

Lemass also saw that a real barrier to Ireland’s development was the prevailing sense of pessimism that hovered like a dark cloud over the country at that time. Within six months of his election as Taoiseach he was able to assert in Dáil Éireann that:

“The most encouraging feature in the national situation at the present time is the disappearance of those clouds of despondency which hung so heavily over the country only a couple of short years ago.”

This refusal to accept despondency and the growth of a spirit of national self-confidence were recorded by John Horgan at the end of his biography of Lemass as being some of Lemass’ abiding legacies.

There is a message for us all in how Lemass responded to the pessimism that permeated Ireland in the 1950s in the aftermath of the war. He responded by setting out a pathway down which he wanted Ireland to proceed. Most importantly, he knew what he wanted to achieve for Ireland. He was clear about which pathway he wished the country to take. He wanted to end protectionism, remove tariffs and industrialise Ireland. He wanted to modernise Ireland’s economy. He wanted to move beyond dated and unsuccessful policies on Northern Ireland that ignored unionism. He wanted reunification to be brought about through consent. All of these objectives are now viewed as being the natural and inevitable progression for this country. In truth, there was nothing natural or inevitable about this at all. Ireland could have remained as a subsistence agrarian society with low standards of living because of the absence of natural resources. Also, Ireland could have continued to answer the national question without accepting that it was a question of considerable complexity.

It was Seán Lemass who had the vision to see that Ireland could proceed in a different direction. He set out a pathway for a new, successful, more confident Ireland. He knew this was feasible because of changes that could be implemented by government. He also saw how the world was changing. Respected, older leaders were being replaced by those who saw great opportunities for their countries in a fast changing world. Although Lemass was nearly 60 when he became Taoiseach and had served many years in government in the shadow of Eamon De Valera, he grasped the opportunities that the office of Taoiseach afforded him to lead Ireland down the pathway that contained his very clear political and economic objectives. The term revolutionary is generally applied to the actions of Seán Lemass between 1916 and 1922, but it was the time he served as Taoiseach that was truly revolutionary.

His achievements in modernising Ireland were recognised internationally and in particular by a new young President in the United States. In the 1960s, John F. Kennedy viewed Lemass not as a veteran figure, but as a leader suited to lead Ireland boldly into the modern world. Addressing Dáil and Seánad Éireann in June 1963, President Kennedy said Ireland led by Lemass had:

“undergone a new and peaceful revolution, an economic and industrial revolution, transforming the face of this land… You have modernised your economy, harnessed your rivers, diversified your industry, liberalised your trade, electrified your farms, accelerated your rate of growth, and improved the living standard of your people”.

Welcoming Taoiseach Lemass to the White House a few months later, President Kennedy described Ireland as “a vigorous new country which looks to the past with pride and the future with hope.” He understood very well that Ireland had tremendous potential which Lemass, as its leader, could continue to realise.

Lemass saw Ireland’s challenges as opportunities. He fought in the struggle for Irish freedom and his brother, Noel, paid the ultimate price during that troubled period. More than many, Lemass understood that freedom was not an end in itself. Progress in modern Ireland has been built on the foundations that he put in place. There could

have been further progress, particularly in respect of Northern Ireland, had he been allowed to construct further foundations.

His meeting with Terence O’Neill in 1965 reveals that Lemass was a politician who grasped opportunities and did not over-think their potential negative consequences. This meeting between the two political leaders contained high political risks for both. We know from state papers that Ken Whitaker brought O’Neill’s private secretary, Jim Malley, to see Lemass on 4 January 1965, with a personal message from O’Neill “that a fresh approach should be made in the matter of co operation between the two parts of Ireland” and extending an invitation to Lemass to visit Belfast as his guest. Lemass immediately accepted and agreed to a date the following week. It was only after accepting that he informed his cabinet colleagues.

Whitaker’s personal account describes O’Neill welcoming Lemass and suggesting that the historic meeting merited champagne. Lemass told him that he long wanted such a meeting to “explore the possibility of practical co operation in the interests of the whole of Ireland”. At the meeting in Stormont they discussed the joint promotion of tourism, cross Border exchanges of pupils, teachers and scholarships, cost sharing in the health services, the elimination of wasteful bidding for outside industrial investment, joint agricultural research, a reduction in tariffs and electricity cooperation.

A few weeks later O’Neill visited Lemass in Dublin to continue their talks. Ultimately, their vision of increased co-operation and cross-border activity was blocked and destroyed by hardliners. Regrettably, the rest is history. How different the history of Ireland may have been if their vision in 1965 was allowed to become a reality.

Today, Seán Lemass’ legacy lives in the investment that Ireland has made in the knowledge and skills of our people; in Ireland’s active role in a strong European community of nations; in Ireland’s pro-enterprise economic policies; in Ireland’s cooperation with all communities in the North; and in the quest for enduring peace

and prosperity on our island. Above all, the Ireland Lemass strove to create was a land of freedom and opportunity. Access to education as a right, the owning of one’s home, and the prospect of realising one’s full potential were the cornerstones of Lemass’ policies. They were Republican policies.

Today, as was the case in the mid-1950s, there is a certain level of despondency about problems that appear intractable, whether they centre on the challenges manifested by the pandemic, the environment, housing for young people or Northern Ireland. The most important message we can all take from today’s anniversary, and the message Seán Lemass would want us to take, is that the same vision and drive that he showed as Minister for Supplies after the economic war and the leadership he displayed as Taoiseach in the 1960s are needed today more than ever.

Lemass would meet with relish the challenges that now confront Ireland. He would see the great opportunities they present.

If we are true to his legacy, so must we.